In an earlier post we talked bruises in marble, which are the bane of modern marble sculptors. They’re like a pimple on your sculpture’s nose and there is no effective makeup for marble.

Surprisingly, bruising wasn’t an issue for the ancients. In fact, as we’ll see in a different post, the available carving techniques prior to the classical period left the surface of the finished sculpture essentially one continuous bruise, and even in classical sculpture, the delicacy of the surface was far less important than it is to modern sculptors. The ancients had a profoundly different understanding of the surface of a sculpture.

Paint

The issue is not just bruising. There is a wide range of things you can do with the surface of marble that the ancients were largely indifferent to because they painted their sculpture. One of the striking differences between sculpture of the ancient world and sculpture of the Renaissance and later movements is the relatively plain surface of ancient sculpture.

Because of their great age you can’t always be sure what the surfaces of Greek and Roman work were like when they were new but they clearly didn’t strive for the exquisitely modeled and polished surfaces that were brought to such a high degree of perfection in the Renaissance and later periods. Sculptures from the classical period tend to look more like limestone in that the potential translucence of marble is ignored. Their surfaces are quite matte, almost like gesso. In contrast, most sculptors in marble from the Renaissance onward have taken enormous care with the surface, manipulating it to give the translucence of skin, or to achieve rich textures for hair, textiles, leather, etc.

In pre-classical sculptures the matte quality is demonstrably due to bruising over the entire surface. (How we know is an interesting story for another time.) In high classical sculpture it is less clear, and there isn’t a lot of literature on this, but the surface of almost all ancient sculpture is similarly quite matte, unlike anything we see in recent centuries. Classical sculptors dealt almost purely with the literal three-dimensional aspect of the stone. The delicate surfaces that Renaissance and later movements employed would have been irrelevant or even distracting under the paint.

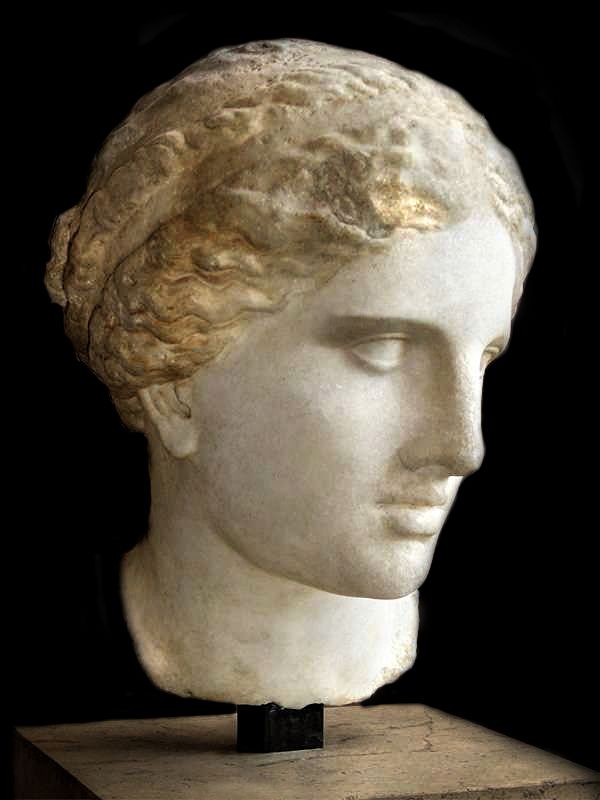

Compare the delicate modeling of the stone in Michelangelo’s Pieta below to the Aphrodite above. Aphrodite is essentially a canvas for paint, while the surface of the pieta is exquisitely modeled, and highly concerned with the highlights and shadows. Michelangelo’s obsession with drawing is easy to understand when you compare his carving to classical carving.

People

A living person is never still. Even a person holding as still as they can is in constant motion. People breathe and the pulse beats in their throat and temples. The entire body responds to the pressure of each heartbeat. Eyes flutter under their eyelids.

Similarly, the idea that we humans have a particular color is defective. Blushes and pallor wash over a person face and body. Human skin doesn’t simply reflect light from the surface like paint on a car; there is a sub-surface scattering of light that softens our appearance, and as we look closer and closer at a person’s skin it becomes impossible to say what color it is. Skin seems to contain every color. Some of the many optical dimension of skin are more obvious with the pale skin of people of European origin, and others are more prominent in darker skin, but the principle holds for people of every color.

You see how much of our visual essence exists in time, motion, and color, rather than purely in form, when a person dies. A person who has just died doesn’t physically change size, yet they seem to suddenly shrink as the subtle movement vanishes, the color leaves the skin, and the tension goes out of their face and limbs. The difference between a sleeping person and a dead person is uncanny because, although they are completely changed, it is hard to say exactly what is different. One way to see how complex color in living skin is, is to compare the skin of a living person to a wax candle of similar color. The wax, which is similarly translucent, lacks the complexities and dynamic quality of living skin even though, at first glance, the color is similar. Starting at the instant of death, the dynamic components of appearance vanish very quickly, and the deceased person’s skin becomes very wax-like, as thought they become a model of who they were.

The corollary is that if a sculptural representation of a person were exactly faithful to the person’s literal form and dimensions at any particular instant, it would appear shrunken and dead. You see this clearly in plaster castings of people’s faces. They look neither like sculpture nor like living people. Instead, they look shrunken and ghastly. And it’s not just faces; much the same is true of castings of hands and other body parts. Sculptors know this. For a sculpture to look life-size, it must be significantly larger than life and all of the features exaggerated.

In addition to the form of the stone, ancient sculptors had paint to help make up the sensory gulf between three-dimensional stone and the many dimensions of a living person. The allowances that they made for subsequent painting informed their carving. The main challenge for sculptors of the Renaissance and later generations, who were limited by convention to monochrome stone, has always been to somehow make up with pure form for the absence of all of the other components of a subject’s visual force.

Displayed as intended, portrait sculptures look more vivid than life, but try the experiment of having someone put their face directly next to a “realistic” sculpture of a person of similar age and sex. The sculpture, which might seem extremely lifelike and vital by itself, suddenly seems grotesquely exaggerated in comparison to the slightness of a living person’s features. This is true of the figure as well–the proportions will be strikingly different from life, and they often diverge the most in sculptures that seem the most convincingly lifelike.

The Return to Classical Style

Mary, in Michelangelo’s Vatican Pieta (1498-1499) is not verist by any stretch; in fact, her face in particular is idealized in a way that almost hearkens back to the medieval but her flesh is exquisitely modeled and the stone is luminous, giving her vitality despite her ghostly pallor and highly artificial form.

Your eye accepts that she is realistic, but if you look at the sculpture dispassionately you can see how bizarrely unnatural is her form. If she came to life, her appearance look freakish. Her head is tiny compared to either her shoulders and neck, or to her height but overall, she is mountainous compared to her son. Her hips would have to be about three feet wide for the sculpture to make anatomical sense. Look at her hands—the natural maximum spread of a person’s four fingertips is about the same as the distance from chin to eyebrows, yet the spread of Mary’s fingers under Christ’s arm is as wide as from her chin to mid-forehead and she isn’t even stretching. Her hands, as well as her shoulders, are far larger than those of her 33 year old carpenter son. Not least, she looks a tad young for a woman with a son His age. She would be at least fifty, but she is depicted at an age that would make sense for a nativity. Yet our eye accepts it all as realistic. You can zoom into this Wikiart link to check it out in detail.

Contrast Mary’s face with the head of Aphrodite by Praxiteles c. 350 BCE which functioned as the ground for paint. Aphrodite is simpler because the Greeks had color and modeling applied with the brush to add the vivacity that Michelangelo had to achieve purely with monochromatic stone.

In general, classical figures were sculpted to a canon of proportion that, while idealized, much more closely approximated reality than Michelangelo, who had one foot in the High Renaissance and the other in Mannerism, often did.

This is not just a quirk of Mannerism. The characteristic is inherent in marble sculpture from the Renaissance and later. The form of an effective sculpture cannot be anatomically correct if it must also do the work of color and movement.

Back To The Romans

The Romans came to international power long after the classical Greeks had yielded to their Macedonian country cousins. Under Phillip and Alexander, Macedonia had conquered most of the known world, leaving Greece proper greatly diminished as a political and military power, but their culture and aesthetics transplanted far and wide.

When the Romans took over the Mediterranean world they superficially adopted the styles and conventions of the Greeks, but they were a very different people. The Greeks were extraordinarily religious and tradition-bound. Their physical world was so saturated with their religion that there was no clear boundary between the two. This stream, or that grove, within the walls of their city, were to the Greeks the actual place where mythological events had occurred. The Greek myths weren’t myths to the Greeks; they didn’t take place in a Neverland of long ago and far away; they were as real as the land they lived on.

The Romans, in contrast, were a practical people who borrowed nearly every aspect of their culture and religion from elsewhere. They carted home to Rome the religious idols of each nation they subdued, and worshiped an amalgam of the religions of all of their subjects. Indeed, one of the main reasons for the enduring hostility of the Romans to the Jews and the Christian cult that spun off from Judaism was the steadfast refusal of the Jews to provide an idol for the Pantheon. The refusal of the Jews to merge into the sprawling state-sponsored entity that was Roman paganism was seen as an ongoing act of rebellion. (Judaism was almost unique in having no idol or cult image and in fact, specifically forbidding such.)

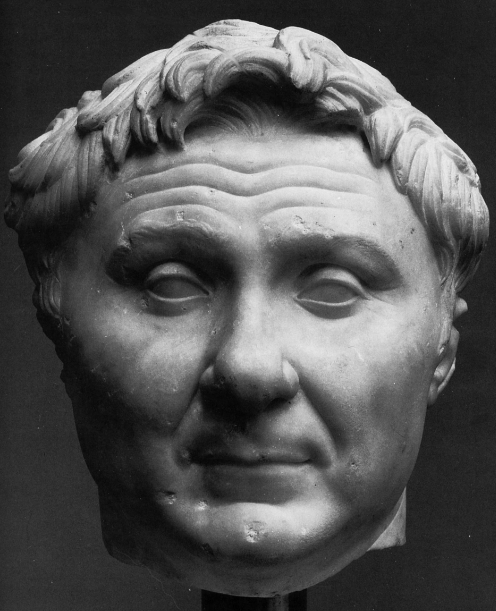

Roman art took on the superficial forms of Greek sculpture but their true bent was verist, the famous “warts and all” style, a sensibility alien to the Greeks.

Roman portraits weren’t at all idealized. The head of Pompey on the left is an excellent example. Yet despite the realism, the surface is essentially matte, like the ground of a painting because it literally is the ground of a painting. Vivacity would be added to the form as color.

The Roots of The Modern View

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 to 1680) was born 123 years after Michelangelo and exemplifies the next great step in sculpture.

Contrast either Pompey or Mary with the closeup of Bernini’s bust of Scipione Borghese, Pope Paul V (1621). The bust is completely unlike either. It is exquisitely carved but it isn’t polished into otherworldly perfection like Mary. Like the head of Pompey, it is verist. Every wrinkle shows, but unlike the head of Pompey, it was clearly not made to support paint and in fact, could not be coherently painted. Bernini does something truly remarkable here.

Light itself is sculpted in the eyes of Pope Paul V.

The representation is extremely convincing despite being completely unrealistic in terms of the bare physical representation. The Pope is not in some abstract, undefined location. You instinctively perceive that the Pope is indoors under artificial light. You can see it by the pupils with the gleam of a candle. Nobody’s pupils look like that in daylight and unconsciously or consciously, we know it. More subtly, note the incised ring around the pupil. There is nothing like this in a human eye. With this trick, Bernini has literally sculpted the color blue.

Note the fine wrinkles around the eyes and the delicate indication of moisture on the tops of the lower eyelids, and the pores in the Pope’s nose and cheeks. (This was probably done by first smoothing the stone, then striking the surface with a wire brush or similar instrument to produce the minutely punctured texture, before lightly finishing again. There are chemical tricks involved in this kind of thing as well, but we can look at that in another post.)

The bust isn’t just a large piece of stone shaped like a person. The artist as sculpted not only light and color, but the abstraction of the subjects location. You feel as though you are in the presence of the live subject.

Nothing like this illusion of life exists in the art of the ancient world. Indeed, nothing like it existed in the Renaissance or even in the Mannerist period.

Only with the Baroque do Western artists begin to step away from the literalness of their media in this way. Always before, sculptors had represented pure form, but with the generation of Bernini, sculptors begin to transcend form and use stone to represent the immaterial. The sculpture of Pope Paul V is a modern in a way that would have been incomprehensible to any previous generation of artists.

This new way of looking at stone never disappears, not even when Neoclassicism comes along a century later, with the exaggerated classical motifs of artists like Canova. It peeks out from beneath the classical formalism of artists like Houdon and Clodion, because the project of reviving the long dead classicism without color is fundamentally inconsistent.

The End of an Age

Edward Onslow Ford’s 1895 “Study of a head: still as a bud whose petals close.” is a exquisite minor piece from a poignant moment in the history of art.

Ford was a member of the New Sculpture movement, a generation of English sculptors who sought a path for sculpture in traditional media that would not be on what they felt was the ultimate dead end road of Victorian sculpture.

The New Sculpture movement stands at the very end of an evolution that had been evolving for five hundred since the beginning of the Italian Renaissance. The final collapse of rule by the landed aristocracies extinguished the dominance of the academies that were their aesthetic arm, and with it came the end of of Beaux Arts. This would create a discontinuity in the sculptural tradition that is as profound as the one that came with the shift from the classical world to the Medieval.

The material scale of the change is often under appreciated. Sculpture was in a strange place at that moment in history because of the sheer scale of the 19th and early 20th C. boom in classical-style building. There was more sculpture being made in the years around the turn of the Century than ever before in history, but paradoxically, it seemed to be ossifying around a style that the onrushing industrial age was rapidly rendering hopelessly anachronistic. The artists of the New Sculpture movement sought to revitalize sculpture by making it more human and intimate.

Ford is perhaps best known for his Shelley Memorial at Oxford, but the small, quiet piece shown below could well be regarded as the culmination of the post-Mannerist handling of marble, the dawn of which we saw in Bernini’s Pope Paul V.

Ford doesn’t ape the classical. He uses the translucence of the marble, its color, subtle exaggerations of form, the precise degree of polish and other properties to make the stone itself appear to almost be alive. There is no trace of the stylized mock-classicism that the New Sculpture artists found inhumane. We often associate verism with physical imperfections, but the essence of verism isn’t the warts; it’s about fidelity to life. The piece quivers with life, utterly gorgeous yet without idealization.

Ford is a perfect endpoint for the history of marble sculpture rooted in the classical, because with Ford’s generation you have traveled as far as you can get from the classical tradition without making a clean break.

This piece would have been incomprehensible to the Greeks for many reasons, but above all, because it is so intimate. Classical Greek art wasn’t about the person; the gods and goddesses were not individual people distinct from the attributes of godhead. Moreover, disregarding the subject matter, the carving itself would not have made sense to the ancients. They would not have known what to make of such extraordinary subtlety employed to make up for the entirely artificial constraint of working in monochrome white. Even the famously verist Romans would have found this mystifying.

Ford and his generation are the endpoint of the five-hundred year long revival of the classical tradition. Beaux Arts architecture would be a casualty of the Great War, and with its passing, the tradition was cut off from its roots.

Even today, more than a century later, marble carving goes on, but the aesthetics are profoundly different, looking back on the tradition founded in the Renaissance, across a dislocation that is nearly as great as the gulf across which Renaissance artists looked at the Classical world.