Neoclassicism is dead and buried but serious sculpture must forever acknowledge classicism’s ghost, if only by whistling past the graveyard.

Classicism has always been a Rorschach test for cultures. Generation after generation adopts the symbols and styles of the Athenians of the Fifth Century BCE, but each generation does so in a way that says more about itself than it ever can say about the Greeks. In what kind of culture could pagan Romans of the Republic, Italian Christians of the Renaissance, atheist French Revolutionaries, and 19th C. Germans all see their own reflections? When Augustus became the first Roman emperor the golden age of Greece was already as remote in time as the Enlightenment is from us today; empires had come and gone. What was once the autochthonous culture of the intensely religious Greeks had by Augustus’s time been for centuries the common property of educated people throughout much of the known world. The Greek language had come to occupy a place much like the place English has in the world today. (England is not among the five countries with the largest population of English speakers. These countries are: the USA, India, Pakistan, The Philippines, and Nigeria.)

Among the inheritors of the classical style, white marble has always been the preeminent medium. But here’s a question: what do you think was the most respected sculptural medium in classical Greece?

Marble

Obviously, I wouldn’t bring it up if the correct answer were the austerely beautiful marbles that we all know so well. Actually, only a minority of the “classical Greek” sculptures that we know date from the classical period in Greece. Many are copies made by the Hellenistic Greeks centuries later for export and many more are copies or copies of copies made by Romans later still. When the Acropolis was rebuilt, its sculptures were still the one-of-a-kind sacred objects of an intensely religious, relatively local culture. By the time Rome became power, sculpture was big international business with busy workshops duplicating famous pieces to order for customers all over the Mediterranean.

While we’re on the subject, we now know that Greek and Roman marble sculpture was usually painted. The major load-bearing elements of temples were generally left white, but the decorative and sculptural elements of the temples were intricately painted too. The Greeks and Romans loved color.

Not only was marble carving not at the pinnacle of prestige, in fact, the great painters of marble sculpture in the classical world were sometimes more celebrated than the sculptors themselves.

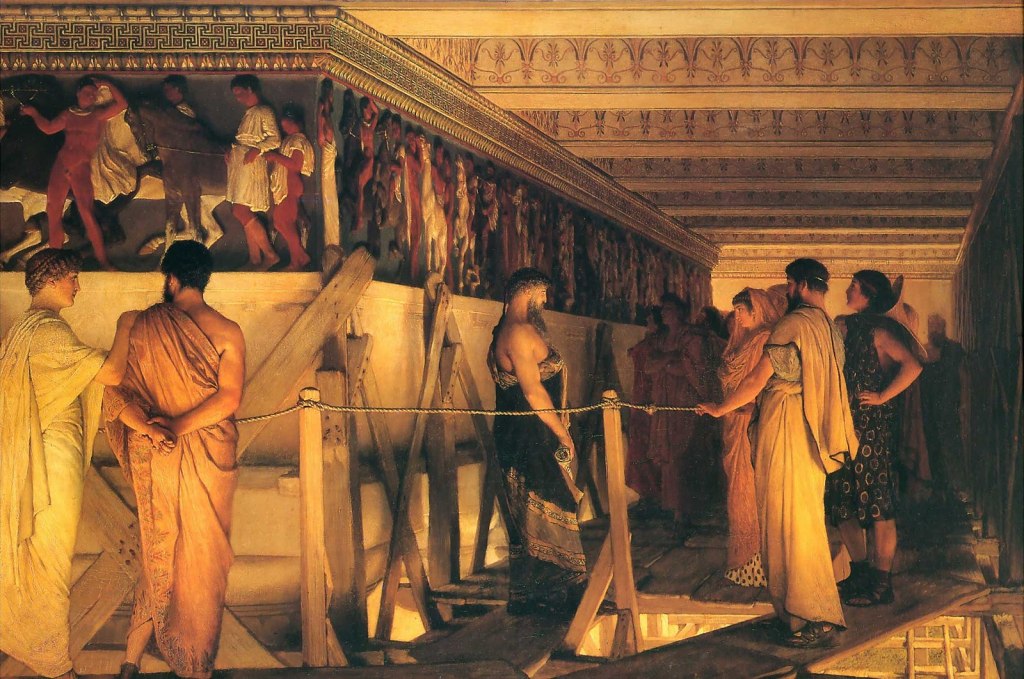

Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann have reconstructed examples of ancient polychromy of which a quick glimpse can be seen here. Their colors are derived from the chemistry of trace remains and lack subtlety but they give a good idea of the exuberance of the painters. Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s luscious 1868 Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to His Friends probably gives the flavor of the polychromy of the Parthenon frieze with less accuracy than the Brinkmanns but perhaps with greater truthiness.

Bronze

Most people’s second guess as to what would be that the most celebrated medium is bronze. Sadly, very little bronze has survived because the metal is so very useful. Not the least of the risks was that anytime there was a war, bronzes were liable to be melted down to make weapons. Bronze seems to have ranked higher on the aesthetic totem pole than stone but it wasn’t the pinnacle either.

Chryselephantine

At the top of the Greek sculptural status heap was chryselephantine, a medium that many people today have never heard of (unless they happen to be from Nashville TN) because only a handful of damaged examples from the ancient world survive.

It is not surprising that it has almost all vanished, because the name comes from the Greek words chrysos and elephantodonto, gold and elephant teeth, aka ivory. Works of chryselephantine were elaborate assemblages constructed over a wooden core, with the flesh being carved in ivory and the rest typically made of bronze and gold and decorated with elements of precious and semi-precious stones, glass and other luxurious materials.

The medium was much older than the classical period. The few extant fragmentary examples date from the Greek Archaic period but the style may be older still; the Minoans on Crete made sculpture of ivory and gold at least as long ago as 1500 BCE.

The example on the left is Archaic Greek, predating the beginning of the classical period by more than a century. The stylized facial expression, particularly the smile, tells you instantly that it is pre-classical. This sculpture and a few similar fragments survived because they were damaged by a fire in the temple of Delphi in the mid-Fifth Century. As it was forbidden for religious reasons to sell or transform the holy relics in any way, they were buried in a sacred dump, gold, ivory and all, and ultimately forgotten until excavated in modern times.

Athena Parthenos

The Greeks produced chryselephantine pieces in various sizes but the most famous works were huge. The chryselephantine statue of Athena by the sculptor Phidias, completed in 438 BCE and housed in the inner sanctum of the Parthenon, was almost 40 feet tall and stood on pedestal ringed with a frieze of bronze figures illustrating a critical moment in the foundation myth of Athens, the sacrifice of Chthonia, King Erechtheus’ youngest daughter. At her feet was a broad reflecting pool that doubled her splendor and simultaneously provided moisture to help preserve the ivory. To give a sense of scale, the miniature statue of Nike, the goddess of Victory, that stood on Athena’s outstretched palm, was itself slightly larger than life.

The structure of the gigantic statue was made primarily of wood. Sources are not precise or consistent about the construction but many resources use the word “core” which can be misleading. The sculpture was hollow, not solid, with a wooden framework supporting sculpted panels that underlay the ivory and gold that was exposed to view. Solid wood would be an unsatisfactory engineering choice because of the inherent instability of wood with respect to humidity. A hollow framework would have been less prone cracking or stressing the surface features by seasonally shrinking and expanding. It would also be far easier to maintain and repair in the event of rot, insect damage, or other problems.

Sources are unclear about the nature of the panels beneath the ivory and gold. They were probably wood, but may have been plaster over wood, or possibly even bronze plates. All three are cited in various sources.

The Varvakeion Athena, pictured above, is believed to be the accurate representation of the appearance of the original in the Parthenon. This marble carving is Roman, made sometime between 200 and 250 CE. It is small–about 41″ high. In marble, Athena’s extended right hand bearing Nike would be not be strong enough to support it’s own weight safely, hence the supporting pillar beneath Athena’s hand; such support would probably not have been required in a sculpture with a wood framework, which would be more resilient and much stronger in proportion to its weight.

The outer sculpture covering, whatever it was made of, was sheathed with carved ivory for the exposed skin of the two goddesses and plates or sheets of gold for most of the rest. In the aggregate the gold weighed more than a metric ton.

The word “plate” suggests something substantial, like the thick bronze of a sculpture, but a ballpark estimate of the square footage of the area covered in gold (at least 1000 square feet) and the volume of the known weight of the gold used (2500 pounds of gold is almost exactly two cubic feet) suggests that the thickness of the gold could not have been more than 1/40 of inch thick at the most and probably less. A fortieth of an inch is about half the thickness of a dime, slightly thicker than the sheet metal that a trash can might be made of. Gold that thin would not be cast, but rather beaten, i.e. repousse.

The gold used for the sculpture amounted to a substantial fraction of the liquid wealth of Athens (or technically of the Delian League of which Athens was the head.) For this reason, the gold elements were designed to be detachable so that the metal could be used to mint coinage in the event of a national emergency and replaced in better times.

This actually happened in 296 BCE, when the statue would have been 143 years old. Athena was without gold plate for an extended period thereafter.

It is not clear exactly when the gold was replaced, but the sculpture was described repeatedly as being sheathed in gold by numerous reliable sources centuries later. In the intervening decades the underlying wood (or possibly bronze) was probably gilded with gold leaf, which would have required only a few pounds of gold.

It is believed that the gold plate was not replaced until after the year 166 BCE when the Parthenon suffered a terrible fire, which at the least severely damaged the statue, and probably destroyed it. It was quickly rebuilt however, probably quite faithfully, as the sculpture was among the most famous in the Mediterranean world. The rebuilt statue was once again clad in gold.

What Was The Statue of Athena Really?

Greek temples were not churches in the modern sense of functioning as a venue for some kind of periodic service or public ritual. They had many functions, but the defining function was to house the sacred cult statue, i.e., the idol, of the god or goddess they were dedicated to.

Paradoxically, the Parthenon, the most famous of all Greek temples wasn’t built as a true temple in that sense because the mighty statue of Athena was not a cult statue that was worshiped as an idol. Athens’ truly sacred statue of Athena was already ancient when the Parthenon and the chryselephantine Athena were built. It was a likeness of the goddess crudely carved from an olive log and said to have been stolen by Odysseus from the citadel of Troy. It was housed in the nearby Erechtheion, the much smaller temple with the famous caryatid porch. If Athena had been a cult statue it would have been an unthinkable sacrilege to design her as a sort of national emergency piggy bank, in Pericles’ own words, “a gold reserve.”

The true functions of the Parthenon were complex. It was built to house the magnificent statue of Athena, and it functioned more generally as the Athenian treasury. It served as a visible expression of the ascendancy of Athens and the Greek victory over the Persians, who had sacked the Acropolis in 480 BCE. But the archaeologist Joan Breton Connelly describes the deeper meaning and purpose of the Parthenon as an expression in stone of the entire foundation myth of Athens. The complex iconography of the statue itself gives Athena’s story but wrapped around Athena is the entire story of Athens and her devotion to Athena made stone.

The End

Athena stood in the Parthenon as empires rose and fell around her until sometime in late Antiquity–the exact date is not known but it was after 350 CE, which is when Constantine made Byzantium the second capitol of a Rome he had declared now Christian.

The statue is believed to have been dismantled and removed to what would eventually be called Constantinople and preserved among countless other famous pagan artworks in the Forum of Constantine. It is believed to have ultimately been destroyed there during the infamous sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 AD. If this is true it would have been more than 1600 years old.

It’s worth noting thought that when we talk about the statue’s age might be a bit like the woodsman who is still using his grandfather’s ax. He’s proud that it’s as good as new after all these years. As well it should be because we take care of it. Dad and I have each replaced the head at least once and the handle’s been replaced I don’t know how many times. Gold is forever, but neither wood nor ivory are.

Reborn In Tennessee

Fortunately, during the many centuries that it stood, it was copied, drawn, and described many times, so we have quite a good idea of what it looked like. It was Athena’s strange fate to be reincarnated in Tennessee of all places.

The Parthenon in Nashville, built in 1897, contains a spectacular full size replica of the original statue of Athena, executed in 1990 by the sculptor Alan LeQuire, who used the numerous extant copies and contemporary descriptions to work out the design. (It is executed in modern materials, not the traditional media.) Note the relative sizes of LeQuire and Nike.

The sculpture is generally felt to be good representation of the original, although some details remain in dispute. The absence of the reflecting pool is a shame–perhaps they will eventually add one.