This blog is about the practical side of sculpture-making but sometimes you need to consider how practices arise in order to understand why they’re taught one way or the other.

The technical process of making stone sculpture in any of the Modernist traditions tends to be very different from the way stone sculpture was made in the period from the Renaissance (Fourteenth to Fifteenth Centuries) to the collapse of the academic traditions after the First World War (1918.) The differences stem from a fundamental change in approach that traces back to early 20th Century politics.

The Paradox

The paradox of figurative sculpture in stone is that while it purports to be all about volume, in the actual making of it, sculpture in stone is arguably the plastic medium that is most purely about the surface.

Modernist sculptors and their descendants have tended to go at a block of stone as if they were painters. I’ll explain why but first imagine how a figurative painting is made. Yes, I know that there are a million ways to paint but generically, it’s usually something like the following.

- The over-all architecture of the image is laid down with drawing media followed by thin washes to establish the light and dark regions and in the process, define the rough locations of the masses. Sometime color is used, sometimes it’s monochrome.

- The major masses are more specifically blocked in within the territories defined by the light and dark areas.

- The blocked-out figure is sharpened and adjusted, with the masses and planes jointly changing in relation to each other and to the background. The border of the figure may expand into the former background in some areas or the background may be tightened up, shrinking the figure in other areas. The boundaries between overlapping features of the figure shift as well. Within boundaries, the forms are adjusted by changes to shading.

- The artist considers the figure and if it’s not just right, repeats step 3 until it comes into focus and hangs together correctly. Only then does the artist move on.

- Detail comes at the end. Working on details too early is a rookie move because each detail pins the fundamental drawing of the figure down in that spot, usually prematurely. The loss of flexibility leads to an unconvincing figure that resists fixing.

For classical sculptors in stone, this approach does not generally work because carving is a one-way process. You can’t put stone back and move the masses around. For any given mass, the momentary surface of the stone is on a one-way trip inward in the general direction of the center of that mass. For this reason (until Modernism) sculptors usually did the 3-D analogs of at least steps 1-4 not in stone but in clay, and often they did all five steps in clay. The typical working process for stone was:

- Create a model in clay (this is steps 1 to 4), typically in 1/4 scale, and cast it in plaster.

- Enlarge the small model it to a full size (clay), make any desired adjustments, and then cast the full size model in plaster.

- Mechanically copy the full size plaster model into stone using a pointing frame, calipers, or some similar technique. After mechanical copying, there is typically as little as 1/32 to 1/16 inch of stone remaining for finishing.

- Finish by hand. Some sculptors took part in this and some did not.

The typical degree of precision used in copying has varied widely from artist to artist, but generally increased over historical time. The Neoclassical movement, which coincides roughly with the First Industrial Revolution, saw an increased reliance on precise copying in part because the market for sculpture increased enormously and multiples became a bigger part of the economics of sculpture.

The Fundamental Difference

The theoretical difference between painting and classical stone sculpture is easy to summarize.

With painting, drawing, wood carving, and sculpture in clay, the essential creative act is generally co-extensive with process of execution. For traditional paintings there is no such thing as a complete plan that can later be executed because the only plan that could fully capture a traditional oil painting would essentially be the painting.

The situation with sculpture in the classical tradition is the opposite; the essence of the piece must be entirely established, or nearly so, before the execution begins. By the time stone or bronze enters the process, the creative act is usually over or nearly so.

This observation can be jarring because we tend think of the essence of art being in the fusion of hand, eye, and material but it’s actually not at all the rule. Take architecture, for instance. Relatively few architects have significant skills in any manual craft of building. Why would they? Once the blueprints are complete, their work is limited to relatively high-level supervision to be sure their design is carried out.

It is surprise to many people that sculptors in the classical styles have typically been much more like architects than like painters. Our romantic mental image of creativity as the fusion of motor skills and senses is so strong that it overpowers some truths that should be more obvious. Painters work with paint, but architects don’t work with brick and glass. The define their 3-D creations on 2-D paper. The drawings are often used to construct miniature wooden models for patrons to consider but the builders just get the drawings.

Likewise, sculptors have typically first drawn on paper and then constructed one or more small scale models. Sculptor’s preliminary models are typically small enough to hold in the hand but the general practice for the last hundred and fifty years or so has been for the artist to create (usually with his or her own hands) a fairly exact model in approximately 1:4 scale depending on the ultimate target size. The version the artist makes might typically be 18″ to 24″ tall. Just as with architecture, the transition from sculptural model to finished sculpture has usually been executed by other hands than the artists. (More on this below.)

The last parallel is that architects rarely design buildings on spec. There is always a patron. Prior to the middle of the 18th Century, this was almost always the case for sculptors as well. Making sculpture on spec really doesn’t take off until the Neoclassical movement, which coincided with the beginnings of the industrial economy that brought unprecedented urbanization and wealth, beginning a centuries-long boom in classical architecture and the sculpture that went with it. With modern industrial economies did the market become large enough for a successful sculptor to assume that he or she could safely execute a piece without a prior commission.

Economics

With this long boom came the practice of sculptors routinely both making sculpture on spec and producing multiples. Formerly, most sculpture was on-off site-specific pieces, but suddenly the world had enough wealth to support an adjustment to the economics. You see this practice explode with the generation of Antonio Canova (1757-1822) The production of multiples and the increasing fame of sculptors went hand in hand because multiples increased the size of the viewership of a sculpture while the resulting increase in viewership reinforced the demand. Canova’s workshop practices are well known and documented because his studio was open to visitors and became almost a required stop for art-minded tourists.

He worked with several assistants who were themselves master carvers, but he is believed to have put significant work into most or all of the finished carvings produced in his name, particularly on the faces and hands.

Practices varied but by the second half of the 19th Century it was common for successful sculptors to have nothing more to do with the execution of a piece once the full size clay model was complete. Many had little to do with it after the 1/4 scale version was complete because enlargement was usually done by skilled specialists.

If a piece was not for a commission that was already paid for, the plaster was typically exhibited pending finding a purchaser who would underwrite the cost of execution. Most of the prominent American, Continental and English sculptors of the later 19th Century worked like this. So strong was the feeling that the sculptor’s job was essentially done with the plaster that some sculptors, for instance, Rodin, often left it up to the purchaser whether a piece would be executed in bronze or stone.

The economics of art almost guarantee that this would be the case. Modeling a figure in clay already represents a significantly larger investment in time, space, and physical exertion than a painting on the same scale. Execution of such a piece, first in plaster, then in stone or bronze, is orders of magnitude more costly still, not just in materials and space, but in sheer person-hours. If a sculptor personally did a significant proportion of the manual work of executing each piece, his or her entire oeuvre would amount to no more than a few pieces that might be spaced apart by years. And the effort would be essentially pointless; the nominal artist’s hand adds nothing special to the process of copying or casting.

Museo Sumaya, Mexico City

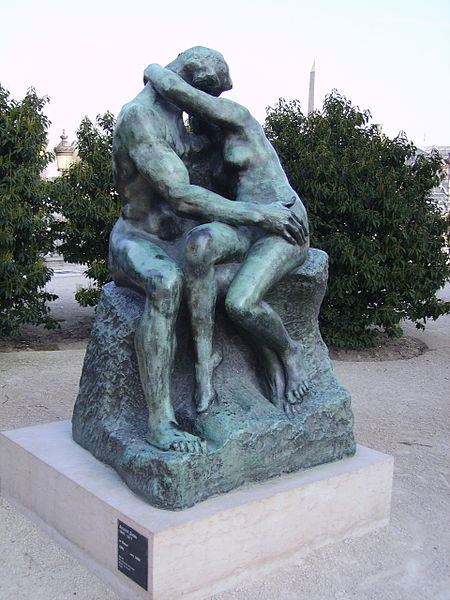

Musee de l’Orangerie, Tullieries Garden, Paris

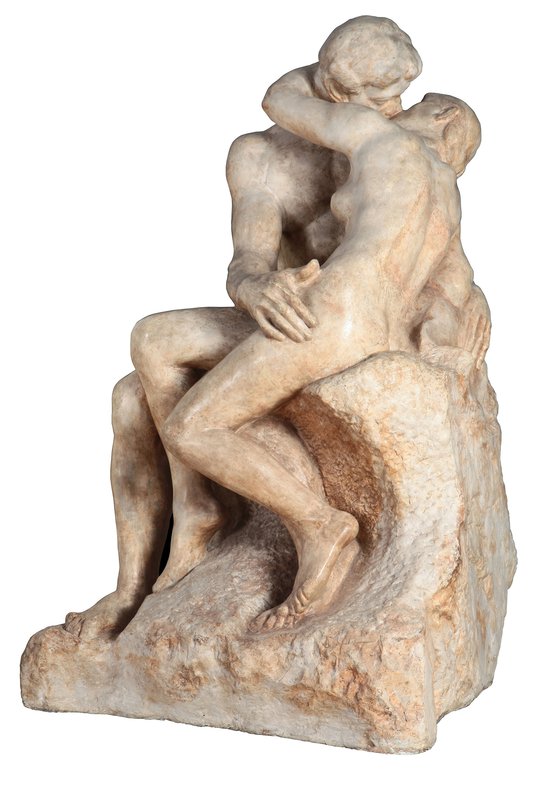

The Tate, London

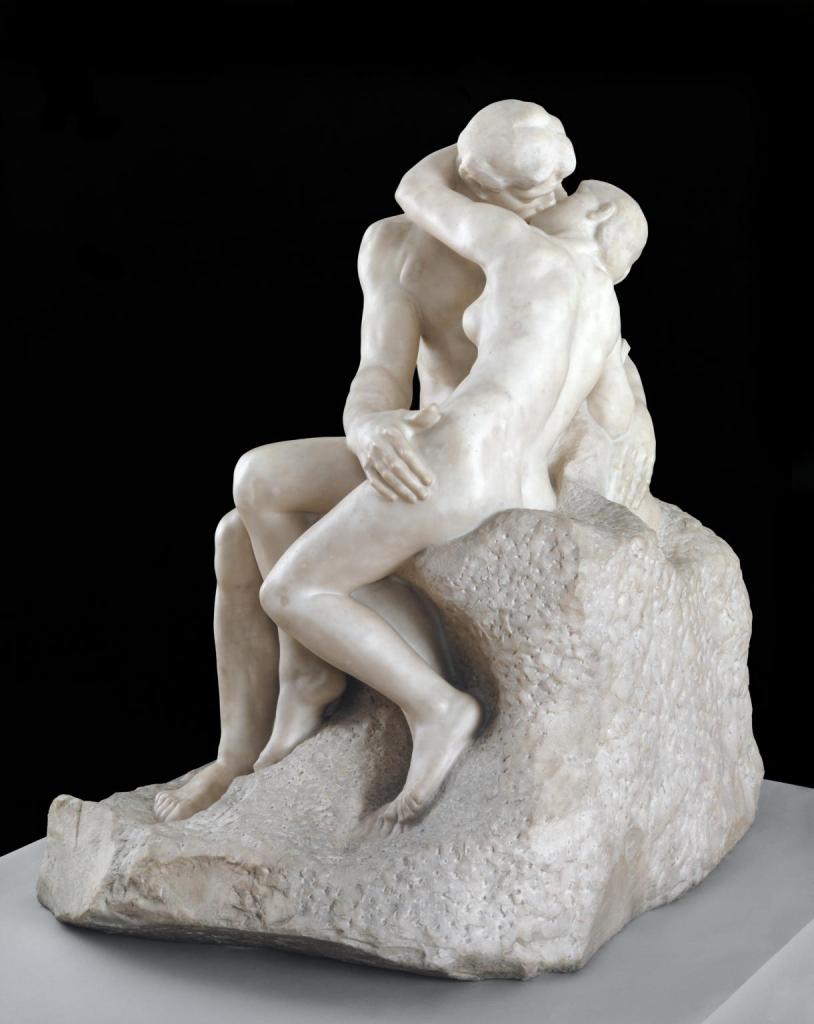

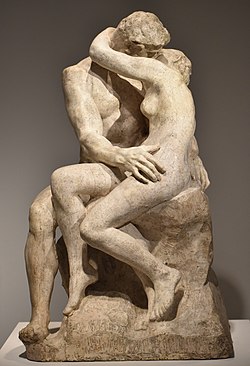

The Rodin Museum, Paris

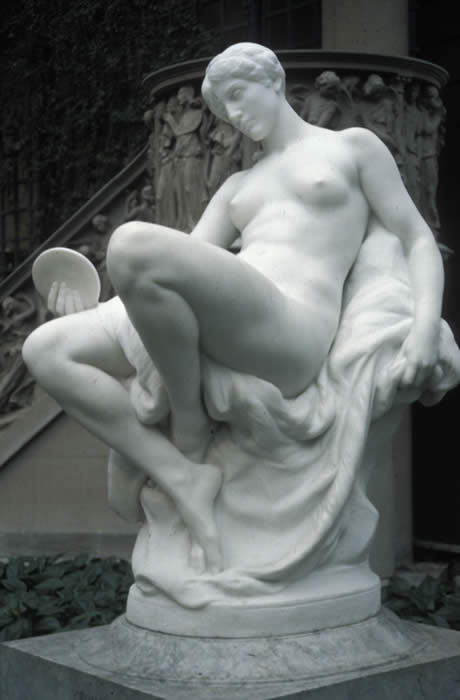

Plaster Casting Museo Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

Terracotta, Museo Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

Even if all the work for which the artist’s hand is not necessary could be farmed out, it would be impossible for a sculptor to reach the levels of success achieved by major sculptors from the Neoclassical on if they did not produce pieces in multiples. Rodin, who was fantastically successful and in enormous demand, often had the same plaster model executed many times in marble, bronze, and sometimes other media, such as terracotta, and often in multiple scales. The technology for scaling-up the original model to full size worked just as well for intermediate sizes. Three full-size marble versions and one somewhat smaller marble version of The Kiss were produced in-house by Rodin’s team and 319 full-size bronzes were produced by the Barbedienne foundry under agreement with Rodin.

My studio-built enlarging machine is pictured above. I’ll do a posting on this at some point soon. At about seven feet long, it’s tiny. I’ve seen old photos of similar machines twenty feet or more in length.

Rodin’s success was over the top, but most other successful artists did much the same. The website of the Gilles Perrault firm has a fascinating piece on the intricacies of the issues of originality in sculpture, particularly in the case of Rodin.

Others sculptors in stone would do part of the work themselves, such as faces and hands, but leave all of the roughing out and most of the less critical carving to assistants (this was Canova’s practice.) Zoom in on the Canova model on the left above–you can see the pins in the plaster that indicated where to rough the stone down to. Bernini (1598-1680) was one of the most skilled carvers who ever lived, but he nevertheless used countless assistants and specialists in carving clothing, vegetation, etc. Bernini was a genius of the same order as Michelangelo. He probably could have executed carvings the way Michelangelo did but he took a different approach to both stone and to his career. Michelangelo worked mostly alone, but Bernini was the head of enterprise that at times employed most of the top sculptural talent in the entire region. It’s unromantic, but prior to the early 20th C. the hand that actually carved the stone was largely irrelevant.

Seal, Furio Piccirilli

Daniel Chester French(1850-1931), most famous for the sculpture of Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial, was the foremost American sculptor of his time. Virtually all of his marbles were executed by the firm of Piccirilli Brothers in the Bronx, NY. The charming Seal, which is in the Metropolitan, is a work by Furio Piccirilli, who with his brothers, executed much of the best known marble sculpture in American history for other artists.

Artists have always been sensitive to the importance of romance. It was not unusual for artists to make a show of their involvement in carving even if they were far too successful and busy to squander their time doing it themselves. Rodin was the unchallenged heavyweight master of modeling in clay. No doubt he could carve with the best of them as well, but in practice he left almost all of it to either in-house assistants or outside services. Even so, he was careful to be frequently seen and photographed tapping away on a chisel.

An Aside

People sometimes panic over issues of who’s the real artist or who get’s credit. Personally, I’m completely comfortable with the idea of artists using hired hands to execute work. I’ve been the hired hand myself many times and have never felt that the piece was anyone’s but the artist paying me. Painters do it too. Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), the greatest master of the Flemish Baroque, kept several studios running simultaneously, each employing multiple painters to whom he offloaded much of the stupendous acreage of painting that bears his name. It’s all nevertheless his work. People who get upset by how the sausage is made shouldn’t go into the kitchen.

What Changed After Modernism?

A strange thing happened to sculpture after the academies were kicked to the curb by Modernism.

Like classical-style sculpture, academic painting was also suddenly rendered irrelevant after the First World War. One big difference was that painting is inherently less tied to architecture than sculpture. Even more importantly, when Modernism broke on the world, painting as a revolutionary activity already went back at least 70 years to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which was founded in 1848. In the decades that followed, diverse extra-academic schools had flourished, often side by side.

Sculpture was in a different boat. So much had sculpture been the handmaiden of classical or classical-like architecture, that it had never developed a robust avant garde in the way that painting had. Thus, the abrupt irrelevance of the academies left classical-style sculpture high and dry (at least in the Western democracies.) Almost by default, the new sculptural practices and styles of sculpture in the Modern age emerged largely from the cultural milieu of avant garde painting rather than as a natural extension of existing architecture and classical sculpture.

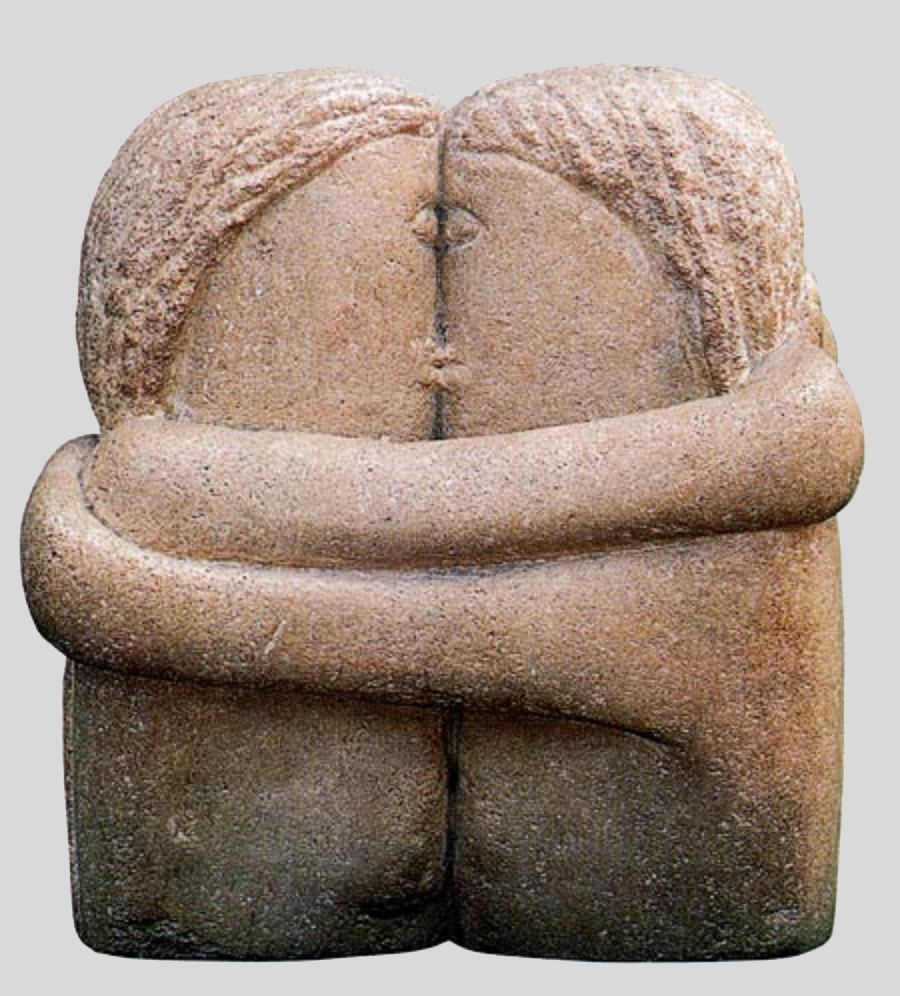

Accordingly, sculpture took on the forms and practices of Modernism, which inclined toward expressionism and abstraction. (The pace of stone carving tended to make it the latter a more natural fit.) Brancusi’s The Kiss (1916), says much about the shift in perspective that came with Modernism. Brancusi repeated this piece many times with slight variations (the one pictured is neither the first nor the last.) There are numerous plaster and stone versions in many sizes but the original was stone, carved directly rather than copied mechanically from a model. We’ll come back to this piece below.

Most of Brancusi’s mature work has the property of being eminently practical to carve directly. The first of the major modernist sculptors, he stepped radically away from the former practices. Tellingly, he worked for a time in Rodin’s studio but left, feeling that he had nothing to add to the old way of doing things.

Onions

If you picture the carving of a head it is natural to think of the process as being like removing layers from an onion. You remove stone all around, layer by layer, until you get down to the head. But the onion model is misleading. It would only work if you were actually carving something as simple as an onion. Imagine carving something with more obvious distinct masses, say, two people kissing. The onion model would lead you to think that you could refine the two heads by peeling away stone around their imaginary centers to end up with a representation of people kissing.

The problem with this mental model becomes obvious the first time you try it. Masses shrink towards their own centers as they are carved, and therefore move relatively away from each other as the layers of stone are removed.

If you get the kissers blocked out so that they look right early on, your subjects will end up air-kissing as they are refined, having shrunk far away from each other. The relative locations of sculptural masses are defined by the precise point of contact between the two masses, locations that are on the finished and polished surfaces at the point of contact. The spatial relationships between the major masses cannot evolve together as the forms are refined.

Even a sculpture as simple as Brancusi’s Kiss immediately runs into this problem. Brancusi solves the problem brutally–he simply incises the line of contact into the stone and bevels back the stone from there, doing almost no further refinement to the masses.

Similarly, the sculptural handling of detail also is inverted from painting. The very first place the carver has to stop isn’t the main masses, but at whatever frivolous detail happens to be in front of them.

This was always well known by figurative carvers, which is why throughout history for most sculptors, the process has been to work everything out in clay, use the clay to make a plaster model, then copy the model, either mechanically or semi-mechanically, into stone. Note that even with his hyper-simplified forms, Brancusi also immediately bumps into the stone carver’s dilemma of having to carve the details first. The tiny vestigial lips of the kissers project in front of the line of contact between the two heads. His defining incision required interruption to allow for the tiny lips. If this fundamental demand of stone is central even in Brancusi’s Kiss, how much central it is to a Rodin or a Bernini.

Contrary to the romantic image, there is no heroic struggle with the stone to wrest the sculpture from the block using hammer and chisel as the painter uses a brush. The actual carving is mostly just work, at least until the last few millimetres, and the more sophisticated the carving, the more this is true.

For this reason, for centuries, personally carving all of one’s own work has been the exception rather than the rule for successful artists. It’s a matter of economics. The dog-work of carving was simply a waste of the sculptor’s valuable time. The sculptor solved all the aesthetic problems in clay and left most or all of the execution to skilled tradespeople.

The Great Exception

Michelangelo is generally acknowledged to be the greatest sculptor since the dawn of the Renaissance. Sculptors have never not been in awe of him, but not necessarily because his work is their favorite. At least part of the awe is for how he made his work.

Michelangelo’s way of working was not at all the process I describe above. He did not mechanically copy a plaster casting of a clay original into stone. It was in fact almost the opposite. Michelangelo usually worked from a small, simplified bozzetto (maquette), and did no mechanical copying but rather worked directly on the stone. He also did all the work himself. Unlike most sculptors, Michelangelo worked front-to-back and he did so in a very peculiar way. Georgio Vasari described the process as being as if the block of stone were a tub full of water and the artist was simply draining the stone away as if he were letting water out of the tub, progressively revealing the sculpture. He worked front to back, so the front-most features would emerge first, fully carved, while the elements of the figure that were just behind them were still completely entombed in stone.

It’s a highly logical way of working for a number of reasons. For one thing, the remaining mass of the block acts as a built-in support for the parts being carved, simplifying the order of carving and reducing the need to leave stone struts in place until the end. For another, it preserves the maximum amount of freedom to recover should the sculptor make a mistake or run into a flaw in the stone. Carving from all around reduces the sculptor’s options to change the design in the event of an aesthetic emergency.

So why don’t all sculptors do that? The answer is that all sculptors aren’t Michelangelo. Working this way implies that the entire sculpture exists in completed form in the artist’s head before the stone is even touched. It’s an amazing feat of imagination. Michelangelo seems to have been able to see, in his mind’s eye, where exactly in the stone each point of his imagined sculpture would finish out and then carve directly down to it.

It is easy to see this process in some of the non-finito slave carvings. You can see how the artist was essentially excavating an already fully imagined surface from the stone. Not a volume but a surface. The slaves were done about 20 years later in his career than the Vatican Pieta, and are superficially completely different in style, but once you have looked carefully at the non-finito work you can almost feel the same mind at work in the Pieta. You can feel that the artist was not somehow working out the aesthetic problems in stone but instead, carving down to a surface he had fully imagined a priori.

So awesome is the physicality of Michelangelo’s work that we tend not to notice how closely related to two-dimensional drawing it is. The normal, literal-minded sculptural process of progressively refining a physical volume from all around is completely abandoned. Instead, he wraps a finished surface, inch by inch, front-to-back, around the imaginary volume contained in the stone.

One of the main reasons that Michelangelo appeals so strongly to recent generations is the powerful feeling for the massiveness of the stone that his process conveys. The modern eye loves the expression of the nature of the medium along with the image itself. The fascinating thing about Michelangelo is that he achieves this sense of physicality through a process of wrapping a surface–an abstraction without substance of its own–around solid rock.

Back to Painting

Modernist sculpture came very much out of the sensibility of painting almost by default because classicism overnight all but vanished for progressive artists. The entire world was in revolution–no young artist of spirit was looking backwards. Modernism was a revolutionary reaction to the academies on more than stylistic grounds; it was political. The academies had been the aesthetic arm of the ancient ruling class that World War One took a wrecking ball to. Every Modernist work of art was in a real sense a revolutionary act.

Modernist tends to be either highly abstracted or expressionistic and to favor an element of the irrational, if only as a style. That puts any kind of sculpture in a quandary, but particularly stone sculpture. How spontaneous and expressionist can you be when you’re literally carving something in stone? Stone sculpture precludes real expressionism during the act of creation but the direct approach favored by the Modernists was nevertheless a stylistic ideal. That’s what we see in Brancusi: that stone sculpture that is not pre-planned in clay and plaster must be limited to either abstract shapes or to simplified figuration.

The entire process by which traditional stone sculpture was made was inimical to the spirit of Modernism. Cultural shifts aren’t simple–to lift a concept from Freud they are “overdetermined” which means that there are multiple causes any one of which might be sufficient to produce the outcome. For multiple reasons, young artists came to be taught to approach sculpture the way they approached paint and Modernism favored winging it. The entire sensibility of sculpture from pre-Modern eras made no sense in the context of Modernism. Accordingly, it was quickly abandoned in the mainstream of high art and the traditional crafts largely vanished from mainstream art education (at least in the US) for many decades. (You can see this in art how-to books over the last century or so.)

Today

Art today has its own cultural and political baggage, but it’s no longer freighted with the epochal struggle to free culture from the domination of a millennium-old hereditary ruling class. The taboos of Modernism mean little more to us anymore than the Neoclassical sensibility of the academies do.

Today, whether a sculptor goes directly at the block like a Modernist or borrows the indirect techniques from other centuries is simply a matter of practicality for the piece at hand, not a statement about politics. The old techniques and aesthetics of sculpture are coming back from their long exile to the totalitarian states to rejuvenate a Modernist and post-Modernist tradition that now stretches back beyond human memory.