I just finished this carved and painted wooden goat head. Despite its conventional appearance, it’s an experimental piece. More on that below. Right now it’s so new it still reeks of lacquer thinner.

The piece shows up in an unfinished state in a couple of earlier posts. I’d love to have shown the process end-to-end but I started this blog halfway into making it and it sat in the studio roughed out for weeks as I set up the blog and did the first few projects/posts.

Experiment One

It’s only tentatively “finished.” The first experiment hasn’t happened yet. The paint is a matte black industrial primer that I love and often use as a finished surface. In this case, however, the primer was intended to actually function as primer. My original intention was to gild, polychrome, and decorate the piece. Unfortunately or maybe fortunately, the primer is so luscious all by itself that I haven’t been able to bring myself to put anything on top of it yet. We’ll see how that goes.

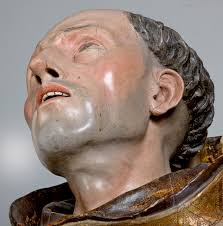

I love polychromed sculpture. There were times in history when polychromy came naturally, but we are in an aesthetically dour and restrictive age. There’s a streak of puritanism under all that pluralism.

The ancients weren’t like us. They painted anything that would hold still; those supposedly austere white marble temples, sculpture and all, were actually as lavishly painted as a Guatemalan transit bus. Interestingly, the only sculpted marble that was usually not painted was the the skin of women. The men’s skin was typically brown, but the women were usually left white.

Polychromy comes and goes. Medieval Spanish colored wood sculpture was very much in the spirit of the ancients. It pops up in the Italian Renaissance and came back in the middle of the 19th C, particularly in France. The under-appreciated American sculptor Malvina Hoffman did some lovely colored pieces in the early 19th C.

The foremost sculptor working with color today is surely Audrey Flack. Her spectacular late-career sculpture may ultimately eclipse her better known paintings, which are associated with the Photo Realist movement of the 1970’s.

How It’s Normally Done

The second way this is an experiment takes a little explaining.

Almost all of my pieces are carved from glued-up wood. That’s what most carvers do. For a host of reasons it is impractical to carve large wood pieces from a raw block cut from a tree. It takes about a year per inch to fully season wood, and this piece is almost a foot deep from front to back. Who plans a project twelve years out during a pandemic? More importantly, wood thick enough to carve something of this size from is sure to check as various regions of the wood dry and shrink at different rates. Yet another reason to glue up a carving blank is to ensure that the wood grain will run in a convenient direction throughout the carving. In this piece, the ears, horns and beard all stick out in different directions. With a single block the grain would necessarily run crosswise to some of these parts making them too weak to stand up to forces of carving and sanding.

My normal procedure, which is what most carvers use, is to first make a clay model, use the model as a guide to building up a blank with a little extra wood all around, then to carve the piece from the blank in a distinct phase.

Experiment Two

I’m a carver more than a modeler. The physical labor of carving pushes you to simplify. The thing I’m after in sculpture is the stillness of classicism without the antique conventions. Classical sculpture aims to capture that instant of stillness that implies both the movement that came before and the one that will follow.

Temple Grandin, the autistic designer of humane facilities for livestock, invented the “cow press,” a walk-in device which calms cows by imitating the pressure the cow would feel from the animals around her in a herd. The resistance of stone and wood are like that; it is a calming force. Clay is too nervous a medium for me.

The flip side, of course, is that pure carving is rigid. It’s like being stuck in a freakin’ cow press. It’s frustrating to not be able to change your mind as painters do.

The experiment was to try to preserve the pacing imposed by carving, but to temper the rigidity inherent in first making a blank that absolutely sets the limits of the finished piece, and then carving within those limits.

Instead, I wanted to try intermixing building up and carving. To preserve the stabilizing, simplifying effect of carving, but allow a little more freedom to adjust the overall form as the carving develops.

This is a very different way to look at making something. Michelangelo, for instance, would not have considered a work made in this way sculpture at all. He considered sculpture to be the art which consisted solely of removing material. Work in media such as clay, in which you could put material back he categorized as a variety of painting.

Pace Michelangelo, I glued up the basic head shape from three band-sawed pieces with sockets cut for the horns and beard, then added horns, beard, and eyes directly without planning it all out with a model. Then I carved a little, added the neck, carved some more, added and removed hair, and generally went back and forth between carving and adding until the basic shape was complete.

It wasn’t clear to me a priori whether this would be a workable process at all, or if it did produce a reasonable result, would it be any different from or better than the results of the normal carving process.

The Miracle of Bondo

The piece was very much a patchwork by the time it was fully built up and carved, so it’s gessoed much like a polychromed medieval carving. In those days, they covered a wood carving that was to be polychromed with a paste of plaster mixed with glue. After it hardened they smoothed and sanded to get a final surface to paint.

Today we have Bondo, which is polyester resin bulked up with powdered talc as an alternative to plaster-based gesso. It was originally invented as a filler for repairing automobile bodywork but it sticks to almost anything, is very durable, and it is compatible with almost any finish. Polyester is the polymer that is used to make fiberglass. Pure polyester resin is the consistency of honey until you add catalyst, which turns it into a brittle, not very attractive, transparent plastic. The added talc gives the polyester bulk, minimizes shrinkage, and makes it easy to carve and sand when it’s hardened.

Right out of the can, Bondo is about the consistency of cake icing, but denser. You mix in a dab of catalyst and apply it like you’re icing a cake, working quickly, because it “kicks” within a few minutes, rather abruptly transitioning from icing-like to a rubbery, congealed state that is not workable. Within a half an hour or so after it kicks it is much harder and you can work it with sandpaper, rasps, or other cutting tools. It continues to get harder for many hours, but it remains permanently workable.

Were The Experiments a Success?

The first experiment hasn’t happened. Yet.

The second experiment is more interesting. The working back and forth gives it a quality I like very much. The result feels more bronze-like and less like a wood carving. To me, that’s a good thing.

The extremely anisotropic nature of wood, i.e., the overpowering fact of its grain, tends to make the form of wood sculpture subservient to the fact that it is made of wood. Grain becomes an overwhelming consideration. Skilled carvers know how to work around it, but aesthetically it is always present and tends to put a sculpture in danger of being an interesting piece of woodwork.

Intermingling the building and the carving gave a pleasing (at least to me) result. It feels subtly more bronze-like than similar carvings I’ve done straight up. Below is a very similar carving from a year or so ago. Very similar, but to my eye, the newer piece seems livelier and less (for want of a better word) wooden.

So I like the result. It was painfully slow, though. I’m hoping the lessons learned will translate into being able to achieve similar results more expeditiously, ideally with a plastic medium such as clay. I’ll keep posting about this.