Classical Greek sculpture arrived abruptly as these things go. In the Fifth Century BCE, naturalistic sculpture suddenly replaced the stylized kouroi that had decorated Greek temples for centuries. The sensibility seems to change overnight. It was the same Greeks and there is no matching discontinuity in architecture, so what happened?

A lot of things changed but the effect of technology on aesthetics tends to get short shrift in art history and rarely has technology’s effect on a stylistic revolution been greater than in the transition to classical sculpture.

Prior to the Fifth C. BCE, the metal of choice in the Mediterranean for almost any purpose for thousands of years had been bronze, which is predominately copper with variable amounts of tin added. Bronze had long been the state of the art for weapons, armor, tools and other implements. The peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean knew about iron and used it, but it was a greatly inferior material. Pure iron is not much harder than soft brass, while carbon-saturated cast iron is so brittle you can break it up with a hammer.

Bronze

Bronze is a wonderful material. It’s easy to make and you can cast it into almost finished form by pouring it into a mold. It’s expensive but you can recycle it endlessly. With the right proportions of copper and tin it can also be made hard enough to hold an edge, so it was revolutionary for weapons and tools. When bronze technology developed in the Mediterranean sometime around 3500 BCE it became the engine of history for thousands of years.

Unfortunately, when it comes to carving stone, bronze is marginal at best. You can work soapstone and some kinds of limestone with it but bronze won’t make the slightest dent in hard stones like granite, basalt, and diabase and it only works for a subset of marble carving tools because it is just barely hard enough for tools that must penetrate, as opposed to crush the surface.

The Belgian sculptor H J Etienne performed a series of experiments in the 1960’s that have often been cited detailing what can and cannot be done to marble using bronze. If you’re interested, Wittkower in his “Sculpture Processes and Principles” explains Etienne’s results more completely than Etienne does himself in his “The Chisel in Greek Sculpture.” Wittkower must have had access to other material by Etienne that I have not found. Both books are excellent if you can find them. People refer to Etienne as “a sculptor” and he was but his own books describe him as “Scientific Officer of the Department of Architecture, Modelling, and Sculpture Division of the Delft Technical University.” He’s clearly as much a scholar and academic as an artist.

The gist of Etienne’s findings is that the punch used at an angle, the workhorse of marble carving, cannot be made to work with bronze. A bronze punch can be made just hard enough to drive a hole straight in at 90 degrees leaving a characteristic puncture at the bottom of a crushed area. As we discussed in the first part of these notes, claw chisels are really just a row of punches fixed together, so they don’t work either. Bronze just isn’t hard enough for tools that work by penetrating at an angle; the tools simply skid off the surface.

How It’s Done Today

The most important class of tools from the classical period until the present are those that drive a spike into stone at a sharp angle in order to pop out a chip of stone. For several reasons, It takes much less impact to remove stone in this way than is required with the 90-degree stroke. Most importantly, with an oblique stroke, the stone on the outside is not supported by a mass of stone backing it. Once the tensile strength of the chip is exceeded at an initial point, the crack easily propagates across the stone and a chip pops free. With the 90-degree stroke, the stone around the point is supported from behind all around. It can only depart the block in a direction opposite the hammer. As the impact involved is applied directly into the stone, rather than obliquely, even for blows of equal power, more force applied into the block. Therefore, with the oblique stroke, elements of the form can be cantilevered away from the main mass without as much risk of the carving forces breaking them off.

The punch, or point chisel, is the main tool used for roughing out the form but it can be viewed as purest form of a larger class of tools that use the same mechanism. A pick is just a punch that is fused to the hammer. Picks are relatively little used today by sculptors but tooth chisels, also known as claw chisels are a mainstay. Claws are used primarily to refine the rough surface left by punching. In its most common form, a claw chisel works very much like a row of from two to seven or so punches. Their most important use is to refine the rough, plowed surface left by a punch. The most common class of claws have punch-like teeth, either triangular or sometimes round if they are carbide tipped. Other claws have chisel-like teeth. Seen close up, the surface claws leave is very much like a miniature version of the surface left by the punch–a narrow line crushed into the stone by the tip surrounded by a furrow of cleanly broken stone. Whereas the furrows left by the punch might be a half-inch deep, the furrows left by a claw might be 1/16 or 3/32 deep. Probably 90% of the stone removed in the course of carving a marble sculpture is removed by either the punch or the claw. Chisels (when used for finishing) can be seen as the limiting case of the claw chisel–infinitely many points leaving furrows of infinitesimal height. They are used to remove the claw marks and then to shape the surface as needed by shaving away thin layers. Note that bronze also makes poor chisels because the angle range at which they works is very limited.

The picture below shows the sequence from left to right. I roughly flattened the entire surface with the punch then moved to the right refining it with three different claws and finally with a chisel on the lower right.

How It Was Done Then

Etienne is emphatic that a bronze tool can’t penetrate obliquely in the modern way, but if you hold a bronze punch at 90 degrees it can poke a hole in the stone and burst out a larger pock around the hole. This of course also bruises the stone below the impact to a considerable depth.

The bronze punch used in this way was the workhorse of pre-classical sculpture. The pre-classical Greeks started with big punches and simply eroded away the mass of stone one spot at a time. As they got closer to the desired finished surface, they punched smaller spots closer together until the entire surface was little pock marks shoulder to shoulder. When it reached that point they switched to abrasives to grind the entire surface down to a uniform un-pocked surface.

There is a subtlety that might not be obvious. At whatever angle it is used, a punch pulverizes the stone directly under the tip, but used correctly, most of the stone removed is broken off, not pulverized. As the punch enters the stone it wedges a wider and wider space for itself. Eventually it gets deep enough that the outward pressure of the wedging fractures the stone away in chips. How the fracturing occurs is different for the 90-degree and oblique strokes. With the 90-degree punch, the stone breaks all around the punch along lines where the stone can’t tolerate the gradient in how much it is compressed. Most of the stone breaks cleanly leaving a large pock, but just under the tip, where punch is simply crushing the stone ahead of itself, there is a void where the tip entered surrounded by a hemisphere of bruising in the remaining stone. See B on the left and A or B on the right above. The result is a surface like the dimples on a golf ball but with a puncture and a bruise at the bottom of each dimple and around the puncture in the remaining stone is a bruised region.

The size of a punch at the extreme tip doesn’t change as the sculptor scales down to finer and finer impacts so eventually, the bruises are no longer separated by fractured stone and the entire surface becomes a field of overlapping bruised regions. But if you cut and polished a cross section, the deep bruises from the early impact would still define discrete round regions penetrating into the stone, with shallower regions of bruising between them.

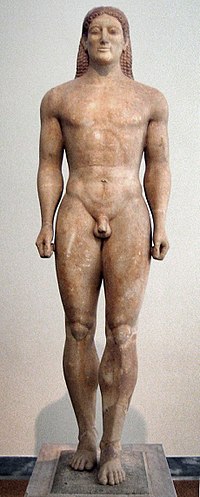

There are surviving examples of unfinished ancient sculpture that show this technique. The picture above shows an unfinished archaic kouros that has been roughed out with coarse punches. After grinding with emery and other abrasives it would have looked much like the one to the left. Note that this piece dates from only a century before the Parthenon sculptures yet you can see that it’s carving was dominated by available tools.

Interestingly, you can see the Archaic carving technique even in some ancient sculpture that was completely finished. The bruising below the punch strikes weathers more readily than undisturbed stone because it’s a nest of tiny cracks that can let in water. Ancient pieces that have been exposed to the elements can thus appear to be reversing the process by which they were carved as the deeply bruised stone erodes away the fastest, giving the surface the appearance of having been roughed out but not finished.

Why It Matters

Analyses of pre-classical sculpture often neglect how the bronze-age carving techniques contributed to pre-classical styles. The extremely laborious process described above works well only for simple forms and surfaces. Firstly, sculpting by pulverizing big pocks in the surface of a stone has an effect similar to pixelating an image. If you pull a pixelated image into PhotoShop you can smooth it out but you can’t recover detail that’s not there. The same principle is at work with smoothing a shape that has been carved with bronze punches, making it difficult and unnatural to carve fine detail because all detail must be superimposed on the simple form by abrasion. Secondly, tools that penetrate, such as punches and claw chisels, can be used with much less impact force. With a 90 degree stroke you need a large mass of stone directly behind the chisel because it takes a tremendous amount of direct pressure to develop the outward pressure that bursts the stone. The oblique stroke requires much less impact and the impact is to the side so it doesn’t require nearly as much mass under the impact. This not only allows the carving of finer detail, it means that projections can be carved with much less support from attachments to the adjacent stone.

You can see the monolithic spirit in the kouros above. This piece is from quite late in the Archaic period and you can feel that the sculptor is moving towards the classical but is held back by the need to keep the limbs attached to the main mass of stone and the feet planted on the ground lest they be broken by the forces of carving. Likewise, the hands are fists because it is impossible to carve fingers with a 90-degree stroke.

Sculptors Still Use The 90 Degree Stroke

Modern sculptors still sometimes use the 90 degree stroke. It works better with high-quality steel punches than with bronze but has limited use because the bruising problem. Therefore it is usually used either early in the process so that there is plenty more stone to be removed below the impact point or on areas that will be left rough. In fact, as I type this I am dusty from using a punch both ways to flatten what will be the bottom of a large block. Bruising on the bottom won’t show and it was useful in removing a mound of stone perhaps six inches high.

You sometimes see the punch used straight in in areas that are left rough as in the base of Rodin’s The Kiss (left.) You can see that the spike poked little holes into the stone but the stone to the side of each hole is fractured, not pulverized. The outward compression caused by the introduction of the spike causes the stone to shear in sort of a bubble around the punch’s tip, popping out chips backwards in a direction opposite the movement of the spike leaving a cleanly fragmented surface. Contrast this with the continuously bruised surface left by a bush hammer. If you know what to look for you’ll often see this in places that have been left very rough.

More About Steel

Steel was the essential material for the kinds of tools that were introduced in the classical period. Steel is iron alloyed with elemental carbon. Steel in one version or another remained the unchallenged state of the art for the next 2400 years until so-called “hard metal” composite materials, notably tungsten carbide, began to make an appearance in the 1930’s. Tungsten carbide tool tips look like metal, but they are actually mostly powdered tungsten carbide, which a ceramic, mixed with a small amount of powdered cobalt and then sintered, which means fused with heat and pressure rather than being alloyed.

Tungsten carbide and similar materials revolutionized the cutting of most hard materials but even today they have not completely replaced steel in marble carving. Carbide is incredibly hard and durable but it is too brittle to be used for a thin blade or a narrowly tapered point. For instance, there is no such thing as a good carbide punch for marble. (Carbide, however, is the material of choice for punches for granite and other hard stones.)

Steel is the perfect middle ground between bronze, which is too soft and hard-metals, which are too brittle. It can be made hard enough, tough enough, and thin enought to penetrate marble deeply at a low angle. This lets a sculptor drive the punch across the stone leaving a deep furrow without bruising the marble more than a couple of millimeters deep. Steel can also used for sharp chisels that shave away the stone in thin layers, greatly reducing the amount of work that must be done with abrasives. It also makes possible rasps, files and similar tools used to model the surface.

We usually think of alloys as mixtures of metals, but some non-metals like carbon or silicon can also be blended into metals. Steel can also contain small amounts of many metals other than iron, but iron are carbon are the defining ingredients. If only a small amount of carbon is added, the result is called mild steel, which is stronger than pure iron, but it isn’t very hard and it can’t be heat treated. The structural steel used in buildings is mild steel.

Too much carbon makes iron brittle. Cast iron, with 2% to 4% carbon is an extreme case. It has so much carbon that it remains brittle no matter what and can’t be tempered to a useable toughness for most tools. (Iron with that much carbon it is no longer considered steel.) Steel that can be heat treated for hardening and tempering must be in the Goldilocks zone of 0.3% to 1.7% carbon.

Steel Is Hard In Both Senses

Interestingly, steel-making and steel-working technology was known in India and in multiple locations in Africa centuries earlier, but it was slow to migrate to the Mediterranean for reasons that are not entirely clear.

What is clear is that steel technology is far more complex than manipulating bronze. Making bronze is like making jello. You put the proper proportions of copper and tin in a crucible, heat them up till they melt, then you pour the liquid metal into a mold and let it cool.

Making steel is more like making mayonnaise. You can’t just mix the ingredients together and get steel. There are subtle manual techniques, precise timing and temperatures and much more complex chemistry involved. In most cases, even if you have steel in hand, you can’t get a usable tool by melting and casting it. To turn steel into a tool or weapon the steel must be forged, i.e., beaten into shape while red hot, then softened by a heat-treatment known as annealing, worked with various cutting and grinding processes, and finally brought to the correct hardness via a series of heat treatments (at least two, sometimes more.) There are many techniques for turning raw ore into iron and none of them are obvious.

Reverberations

Steel punches, claws, and chisels vastly reduce the forces that must be applied to stone and reduce the need to always have a column of solid stone between every part of the work and the core of the stone mass.

Introducing the ability to carve delicately changes an entire ecosystem. One of the biggest changes is in how the sculptor looks at the mass of stone. The archaic sculptors carved like they were making a Bill Ding. The drew the silhouette of the sculpture on the front and side of a rectangular block and chipped down to the projected shape from four sides. We know this from incomplete works that still exist, but even if they did not, you can almost feel the rectangular block when you look at a kouros. It is the natural way to carve when you must work within a monolithic form. It’s not that it would be logically impossible to work in some other way, but why would they?

With the introduction of the ability to truly carve stone, the geometric genius of the Greeks comes into play. This was the Greece halfway between Pythagoras and Euclid. Suddenly they could work in clay and use the geometer’s intellectual tools to define arbitrary shapes in stone. (We don’t know in detail what geometric techniques they used, but traces from mechanical measurement processes remain on pieces from this period.)

Conclusions

The Fifth Century BCE is a watershed in history, but sculpture seems to light up with an abruptness that is striking even against that background. Architecture, literature, mathematics, and other arts blossom but they don’t seem to undergo the abrupt and revolutionary change that sculpture does. My belief is that the difference hinges on technology. With steel tools, for the first time, sculptors could truly carve; they weren’t limited to the relatively monolithic forms that were imposed on them by high-impact bronze tools. The single change, the ability to carve obliquely, snowballed into a host of technological and aesthetic shifts that reinforced each other, transmuting the way the Greeks treated stone within little more than a single working lifetime.

You can feel the humanistic impulse gathering in late archaic pieces, but the technology clearly isn’t there. When it does arrive, the stiff forms of archaic Greece transform into the fluidity of the classical period almost overnight.